Hook rotation is one of the most talked-about concepts in carp fishing — and one of the least understood. Most anglers can describe what they want a rig to do (“turn aggressively”, “flip fast”, “catch hold”), but far fewer can explain how or why that happens.

This article breaks hook rotation down into mechanics and forces. Not fashion. Not opinions. Just what is physically happening when a carp sucks in, tests, and ejects a hookbait.

Why “Hook Rotation” Is Misunderstood

A rig that catches carp is often assumed to be working optimally. In reality, many rigs catch fish despite inefficient mechanics — especially on high-stock waters or during competitive feeding.

Hook rotation is often described as:

- “The hook turning in the mouth”

- “The hook flipping over”

- “The hook taking hold quickly”

These are outcomes, not explanations.

Rotation is not a single moment. It is a sequence of force transfers that begins the instant a hookbait moves and ends only when the hook either takes hold or is ejected.

What Hook Rotation Actually Is (In Mechanical Terms)

In simple terms, hook rotation is the process by which:

- Force is applied to the hookbait

- That force is transferred through the hair or attachment system

- The hook pivots around a point

- The hook point is presented and driven into flesh

For rotation to occur reliably, three things must happen:

- The hook must pivot, not slide

- The hook point must be presented correctly during that pivot

- There must be sufficient resistance at the right moment

A hook that moves but does not pivot is not rotating. A hook that pivots too late is not rotating effectively.

The Critical Forces Acting on a Carp Rig

Understanding hook rotation means understanding the forces acting on the rig inside the carp’s mouth.

Suction Force

When a carp feeds, it creates a rapid inrush of water. This force pulls the hookbait inward, acts primarily on the bait rather than the hook, and is directional but rarely perfectly straight.

If the hookbait is very light or highly buoyant relative to the hook, suction can move the bait without moving the hook enough to initiate a clean pivot. That can delay rotation — or allow the hook to travel in without presenting the point.

This is one reason a spinner rig with a pop-up can be so effective: the buoyant hookbait moves instantly on suction, and the hook is free to rotate aggressively when tension is introduced. However, the same buoyancy can also reduce meaningful resistance early in the sequence, which is why very buoyant pop-ups sometimes produce rapid bites but occasionally shallow hook-holds if resistance is not encountered at the right moment.

Ejection Force

Carp rarely eject baits straight back out. Many ejections are sideways, downward, or combined with subtle head movement. That means rigs must rotate under non-linear force, not just a neat straight pull.

Rigs that look superb in a simple straight-line pull test can fail when the bait is being pushed out at an angle.

This is where a D rig with a wafter or balanced bait often excels. The bait can be taken in and tested with a little more give, then when ejection occurs — often sideways — the controlled relationship between hook, hooklink and bait still allows the hook to pivot and take hold under off-axis force.

Gravity

Gravity acts constantly, including before the take. It influences how the hook settles and determines whether the point hangs down, lies flat, or lifts.

If a hookbait is too buoyant, or a balance is misjudged, the hook can be held unnaturally, reducing the chance that the point is correctly oriented when suction occurs. Conversely, a heavy bait can deaden movement, allowing the carp to mouth and eject the bait without ever creating a decisive pivot.

Resistance

Rotation does not happen in free movement. It requires resistance from the lead system, line angle, bottom friction, or the inherent stiffness of the hooklink.

Without resistance, the hook simply follows the bait. With too much resistance too early, the rig can behave unnaturally and be rejected.

Hook Design and Its Role in Rotation

Hook rotation begins with geometry.

Hook Eye Orientation

The eye determines how force enters the hook. In-turned eyes typically encourage earlier downward rotation, straight eyes offer a more neutral force transfer, and out-turned eyes can delay rotation while improving hook-hold security.

The eye angle shifts the pivot point, which largely dictates whether a hook flips decisively or drags.

Gape Width and Shape

A wide gape does not automatically improve rotation. Wide gapes often require more force to turn, while narrower patterns can rotate faster but may be less forgiving once the hook takes hold.

Rotation speed and hook-hold security frequently work in opposition.

Shank Length

Shank length affects leverage. Longer shanks tend to rotate more aggressively, while shorter shanks offer more controlled, predictable movement.

Excessive leverage can cause over-rotation or awkward hook-holds, particularly when combined with very aggressive aligners or stiff hooklinks.

The Role of the Hair in Hook Rotation

The hair is not passive. It is a force-transfer mechanism.

Hair Exit Point

Where the hair leaves the hook determines how force is applied. Lower exit points encourage earlier pivot, higher exit points delay it, and sliding attachment systems alter when rotation begins.

The exit point is often more important than hair length because it controls the initial direction of pull.

A D rig effectively engineers this behaviour. The relationship between hook and bait is controlled so the hook is not forced to flip instantly. This can be advantageous with pressured carp that inspect baits carefully, as rotation still occurs but later in the sequence, often during the transition from inspection to ejection.

Hair Length (Mechanically)

Short hairs transmit force quickly and promote early rotation. Longer hairs allow the bait to move more independently and delay pivot.

Delayed pivot is not automatically a disadvantage. The key question is whether the hook still pivots decisively before the bait is expelled.

Rig Components That Influence Rotation

This is where many rigs drift into fashion-driven design. Components do not create rotation by default — they alter angles, stiffness, friction and timing.

Shrink Tube and Kickers

Shrink tube and kickers modify the angle of pull. They can help the hook flip sooner, stabilise presentation, or compensate for minor geometry issues.

On a bottom bait hair rig fitted with a line aligner, the aligner’s role is to encourage a controlled pivot once tension builds, rather than forcing instant rotation the moment the bait moves. This often leads to more consistent hook-holds on bottom baits, where the bait itself does not generate movement like a pop-up does.

Aligners

Aligners can increase rotation speed by exaggerating the angle of pull. Used carelessly, they can also promote shallow hook-holds if the hook flips too early or too aggressively before meaningful resistance is introduced.

More aggression is not always better.

Rig Rings and Swivels

Rings and swivels reduce friction and allow movement. That can be beneficial, but too much freedom can allow the hook to follow the bait rather than pivoting independently, reducing the chance of a clean flip under off-axis force.

The spinner rig is essentially an exercise in managed freedom. The hook is allowed to rotate extremely freely, which is why it excels at grabbing hold quickly, but it relies on the system meeting resistance at the correct moment. If the entire setup is too buoyant or slack, the hook can rotate repeatedly without ever being driven in decisively.

Rig Examples and Their Hook Rotation Mechanics

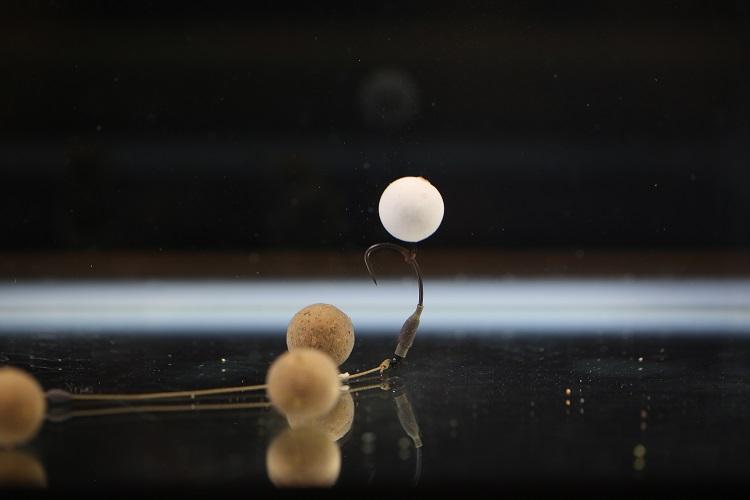

Spinner Rig (Pop-Ups)

The spinner rig prioritises fast, aggressive hook rotation. The hook is free to rotate independently of the hooklink, meaning rotation often occurs very early in the take sequence, sometimes under relatively light suction.

This makes it highly effective for converting cautious or tentative takes, but it also means that hook-hold quality depends heavily on resistance being introduced at the right moment. Without that resistance, rapid rotation does not always translate into deep penetration.

D Rig (Wafters and Balanced Baits)

The D rig represents a more controlled approach. Rather than forcing immediate rotation, it allows the hookbait to enter the mouth freely and sit centrally during inspection.

Rotation often occurs later, frequently during ejection, when sideways or downward force is applied. This makes the D rig particularly effective when carp are testing baits rather than feeding confidently, and it highlights that effective hook rotation does not always happen during inhalation.

Bottom Bait Hair Rig with Line Aligner

A bottom bait hair rig fitted with a line aligner encourages progressive, controlled rotation. The aligner adjusts the angle of pull so that the hook begins to pivot only once resistance builds.

This slower, more measured rotation often produces deeper, more secure hook-holds on the bottom, especially when carp are feeding confidently and resistance is applied steadily rather than abruptly.

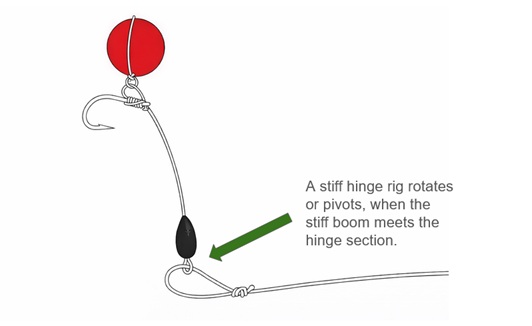

Stiff Hinge Rig (Pop-Ups)

The stiff hinge rig operates on a different mechanical principle to most other rigs discussed here. Rather than relying on the hook eye or hair exit point as the primary pivot, rotation is created at the hinge section between the stiff boom and the flexible hook section.

When a carp inhales the pop-up, the hook and bait are able to move freely because of the short, supple hinge. This allows the hook to drop and orient point-down before significant resistance is felt. The pivot, in mechanical terms, occurs at the hinge junction, not at the hook eye itself.

Once the carp moves or ejects the bait, the stiff boom straightens and introduces resistance. At that point, the hinge can no longer fold, and the hook is driven home.

This explains why stiff hinge rigs are particularly effective for pressured carp and pop-up fishing:

- Early freedom allows natural bait movement

- The hinge creates rotation before resistance

- The stiff boom converts rotation into penetration

It also explains why incorrect hinge length or stiffness can kill the rig’s effectiveness — too stiff and the hook cannot orient, too soft and control is lost.

Bottom Type and Hook Rotation

On firm bottoms such as gravel, clay or hard sand, resistance arrives earlier and rotation happens quickly. Over-aggressive rigs can over-rotate or take hold shallowly in these conditions.

On soft substrates such as silt, chod or debris, resistance is delayed and rotation often occurs later, sometimes during ejection. In these situations, hook weight, balance and hooklink behaviour become far more critical.

Common Reasons Rigs Fail to Rotate Properly

Many liners, missed takes and brief bleeps are mechanical failures rather than simply cautious carp.

Common causes include over-balanced hookbaits lifting the hook unnaturally, excessive separation between bait and hook, overly supple hooklinks that fail to transmit force, components that add movement but remove control, and insufficient resistance at the key moment.

Hook Rotation vs Hook-Hold Quality

A bite is not proof of good mechanics.

Poor rotation commonly produces lip-edge hook-holds, shallow penetration and hook-pulls close in. Consistent, central bottom-lip hook-holds are the clearest indicator that rotation is occurring at the correct time and under the right resistance.

Testing Hook Rotation (At Home and On the Bank)

Basic in-hand pull tests can highlight whether a hook wants to pivot at all and whether the hair or attachment interferes with rotation, but they cannot replicate water resistance, off-axis ejection or the behaviour of a bait in real feeding situations.

In water, movement slows, balance changes and delayed rotation failures become obvious. Many rigs that look perfect in the hand behave very differently once submerged.

When Hook Rotation Matters Less Than You Think

In aggressive feeding situations and high competition, carp can be caught on almost anything. That is why poorly designed rigs still appear to work at times.

As pressure increases, mechanics matter more, not less. Subtle takes and angled ejections demand precise timing and control.

Designing Rigs Backwards: Start With Rotation

Rather than copying popular rigs, it is far more effective to design from first principles. Decide when rotation needs to occur, choose hook geometry to support that timing, match bait buoyancy and attachment mechanics accordingly, and only add components if they clearly improve control or presentation.

This is the difference between rigs that look aggressive and rigs that consistently convert takes into secure hook-holds.

Final Thoughts

There is no best rig. There are only rigs that rotate correctly under specific forces, timing and conditions.

The spinner rig, D rig, bottom bait hair rig with a line aligner, and stiff hinge rig are useful examples because each illustrates a different mechanical approach to rotation — early aggression, delayed control, progressive pivot, and hinge-driven orientation.

Stop copying rigs. Start understanding what they are designed to do — and when.